The World Will Be Saved by Beauty

By Kate Hennessy (2017)

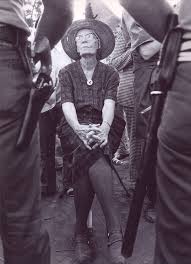

Hennessy, the granddaughter of Dorothy Day, gives us an honest reflection on the life of an exceptional woman: her faith, her work and her family life.

Day is under consideration for sainthood. Pope Francis singled her out as one out four Americans who have made their nation ‘great’. There have been biographies and films, in addition to Day’s own account of her early life, The Long Loneliness (1952). But none of these ever felt correct to Day’s daughter Tamar. Hennessy wanted to write something Tamar might have been satisfied with.

An unmarried woman, Catholic convert, mother of a young child, estranged from her ‘common law husband’ – as Day called Forster Batterham – at a time when women were expected to remain in the home, Day – and the wandering French philosopher Peter Maurin – started the Catholic Worker. Day envisaged a successor to socialist newspapers she had worked on as a young university dropout; Maurin saw the paper as a vehicle for his ‘Easy Essays’ on social justice and faith. The paper was an unbelievable success: circulation rose from 2,500 in 1933 to 110,000 by mid-1935. Voicing the first call in the 20th Century for a ‘green revolution’, Day is a figure who commands awe.

Hennessy draws on private letters, anecdotes, memories and long inconclusive conversations with Tamar, in this detailed portrait of a complex woman. Day is revealed as a loving, but flawed, mother; a woman of intense love and also temper.

Day’s daughter was seven when the first edition of the Catholic Worker was published. In their paper Day and Maurin had called for bishops to look after the hungry poor of the Great Depression. The bishops did not. This led people to turn up at Day’s door asking for help and thus initiated Catholic Worker houses of hospitality, over 200 of which still operate around the world today.

Tamar grew up in these houses, with Day, Maurin, long standing members of the movement and the many destitute people who came seeking sanctuary. Life was hard. As Day commented, they had no need of hair shirts, as they shared crowded rooms, lice and bedbugs with the residents. Speaking commitments drew Day all over America and – painfully – away from her daughter.

Hennessy paints a picture of Day’s extremely practical faith, borne out of the life of a single working mother. Day remarked ‘prayer is my job’ and estimated her spiritual life took ‘three hours a day’.

Day found joy in many things. She loved to be near the sea and returned throughout her life to Staten Island. Despite the increasing pollution of her beleaguered island, she always discovered beauty in it. She read voraciously: counselling Tamar that a good book is something to look forward to at the end of the day – Dostoyevsky was a favourite.

Hennessey conveys a sense of Day as a woman who loved her child intensely – Tamar’s birth was the reason for Day’s conversion. But Day failed, sometimes, to have empathy. At 23, Tamar was pregnant with a third child; in an unhappy marriage; with little money and insufficient heat when it was fourteen degrees below outside. Day advised her daughter to be less ungrateful.

The biography does not shy away from failure and divisions within Catholic Worker houses Day founded. One farm had to be broken up when a member successfully turned the upper half of the property into a sinister cult, which viewed Day as the enemy.

One of the most hopeful aspects of this book is Hennessy’s description of the way in which Day gradually accepted her own limitations alongside her determination to keep working in faith despite impossible pressure. She battled the chaos of the movement and demands of the paper, as well as conflict and isolation in her personal life. When she was seventy-nine, Day commented, ‘faithfulness and perseverance are the greatest virtues…since Christ was the world’s greatest failure.’ Day kept the Worker going throughout World War Two, Vietnam and the Cold War when the world must have felt as if it was falling to pieces.

Day refused to think that the 1960’s enthusiasm for individual freedom and the abandonment of traditional beliefs could offer a path to freedom. In this respect she is a figure of opposition to the 1960’s and how they are viewed now. Day called the 60’s a time of ‘anger and turbulence’.

Hennessy portrays her grandmother as a person of immense talent, who found happiness in relationships with the destitute and with children. She explains how Day managed to remain, despite everything, a lifelong practitioner of ‘works of mercy’. Perhaps, as some of her admirers fear, being made a saint could ‘demote’ Day and obfuscate the significance of her work. Hennessy’s biography is the antidote to hagiography. Her account reveals how an ordinaraily imperfect woman was able to achieve what you could call miracles through religious faith and relentless work.

Leave a comment