-

‘She Never Said Let It Be’

A review of Arundhati Roy’s recent book about her mother… In this memoir, Arundhati Roy turns her attention to her mother. Mary Roy, who died in 2022, was a famous activist and educator who, in 1998, won equal inheritance rights for women in her Keralan Syrian Christian community. In 1967,…

-

The Loss of Bubbe

I am extremely proud that my new story is out today in Jewish Fiction. Benjamin Gold sees himself as the good father rescuing his teenage son from rough kids on the beach. But, feeling the sting of his son’s contempt, Ben is forced to look at himself: how the loss…

-

‘There are tens of millions of Russians who are against Putin…’

Alexei Navalny’s death last February in one of Putin’s gulags was a blow to Russians’ hope for a future peaceful democratic government. But, according to the Guardian, on the anniversary of his death last Sunday, ‘a steady queue of people braved freezing temperatures and possible arrest in Moscow to visit…

-

‘…on those days when you are at odds with your neighbours you are really at odds with yourself.’

Thoughts on the Church of England.. Those running the Church of England have displayed terrifyingly little self-awareness. Knowing about violent abuse committed over four decades by an acquaintance, Justin Welby – in his own words – ‘personally failed to ensure that…the awful tragedy was energetically investigated.’ Still he didn’t choose…

-

Dorothy Day

The World Will Be Saved by Beauty By Kate Hennessy (2017) Hennessy, the granddaughter of Dorothy Day, gives us an honest reflection on the life of an exceptional woman: her faith, her work and her family life. Day is under consideration for sainthood. Pope Francis singled her out as one…

-

New Story on Chestnut Review: mixed-up auto fiction focusing on loss of identity.

And Is It Too Late Now To Learn Hebrew, Hannah Glickstein

-

Emily Is Hearing Voices

Have a read of my new story: a girl struggles to quiet the noise in her mind, whilst all around is silence..

-

Ursula K. Le Guin, Unsurpassed

Reading the Earthsea Quartet is like tuning into a frequency of awareness just underneath conscious thought. It is easy to become immersed in Le Guin’s world of wizards, sodden barren landscapes and dark ancient cults. Because her characters – even the wizards – are totally human. And their experiences are…

-

Some thoughts from Solzhenitsyn

Writing between 1958 and 1968 about his own, and others, experiences of Stalin’s gulags, Solzhenitsyn reflected that – unlike Germany – Russia was unwilling to admit any crimes committed by Stalin. (And still being committed under Khrushchev.) It is worth asking if such a reckoning ever took place. I don’t…

-

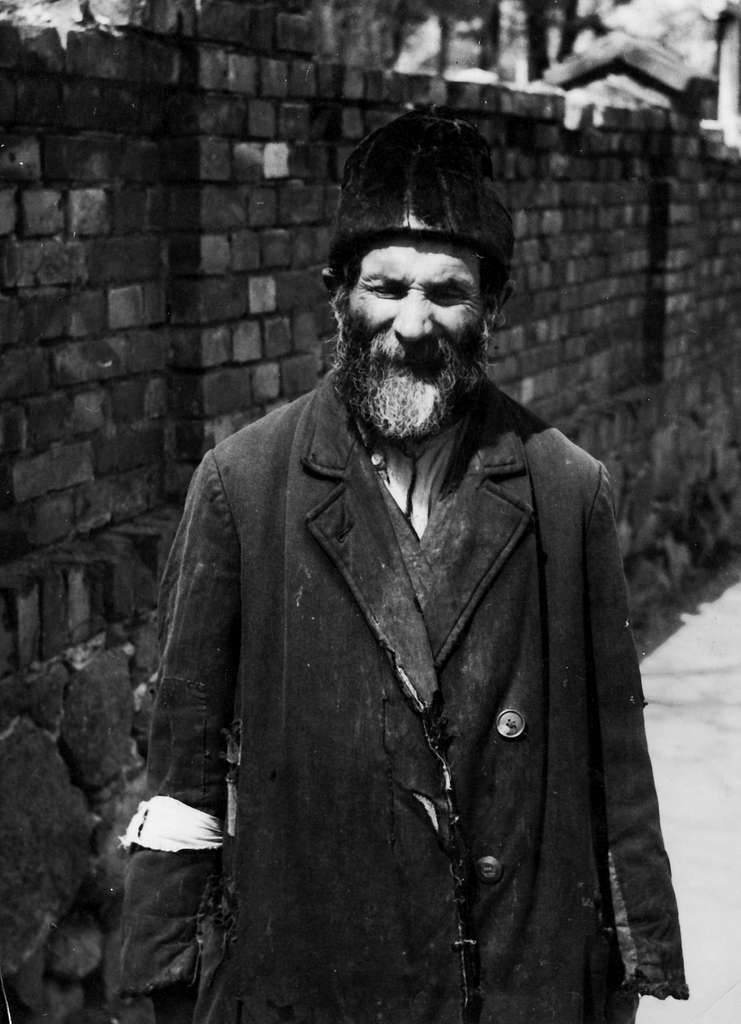

‘We’: Yevgeny Zamyatin

This is Yevgeny Zamyatin’s sparkling, terrifying, portrait of a society committed to “mathematically infallible happiness”; preparing to launch a rocket towards “alien planets” – to either deliver this happiness, or “force them to be happy”. The author was arrested, aged 21, as a Bolshevik student activist in 1905 by Tsarist…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.